Caption information at bottom of page

"Throughout history, deserts have provided a sort of blank canvas onto which people from various cultures, backgrounds, and political persuasions can project a seemingly endless succession of notions, visions, schemes, plans, and desires."

- Peter S. Aragona and Clinton F. Smith, "Mirage in the Making" (2012).

Symbols of the Desert Landscape

A Guide to Vision and Aesthetics

Death Valley, California (?), approximately 1925-1935.

Death Valley, California (?), approximately 1925-1935.

The desert appears as a blank canvas, a tabula rasa of sorts, for the human imagination. Common visions of the American desert landscape, wistfully noting its massive expansiveness, see it as a location filled with uncertainty.

Photography profoundly impacted studies of the desert landscape. Turning the camera toward the desert allowed for the documentation of its atmospheric and geological processes. In the image at left, a photograph of what may be Death Valley serves two objectives. It exists as empirical evidence of the various elevations seen in the landscape. Images like these, while looking scientifically at the desert, have another goal. The rise in elevation in the photograph maximizes gradations of light and dark, accentuating the austere elegance of one lone bush in the foreground. The hazy grayscale mountains in the background gently slope until they meet at some unseen point in the distance. All that we discern at this disappearing point are radiating rays of sunlight hitting the mountains and the wispy bands of clouds in the sky. Even if scientific in intent, this image creates a discernible desert aesthetic infused with the sublime - or the all-consuming awe felt when confronted with such a powerful and mysterious view.

Photographs of desert landscapes oscillate between rational vision and sublime aesthetics. The former points to a logical human eyesight that sees the desert as a subject of scientific expedition and study. On the other hand, the latter gazes at the elemental aspects of the desert that pulse with beauty. Yet, as we see, those two ways of seeing the desert are inseparable, possibly revealing a weakness in our ability to fully perceive this environment - it remains an intractable blank canvas for different ways of seeing.

The photographs in this gallery explore the symbols created to aid in the sense-making of the desert. The title Legend is a double entendre that at first glance refers to the merely informative interpretations of symbols helping travelers navigate rock formations and other notable features. A second meaning sees logical symbols as imbricated in modes of aesthetic interpretation that infuse the landscape with enculturated desires and ideals. In this gallery, there are three sets of legends that address both these registers: botany and the sublime, geology and abstraction, and landscape and orientalization.

Photography profoundly impacted studies of the desert landscape. Turning the camera toward the desert allowed for the documentation of its atmospheric and geological processes. In the image at left, a photograph of what may be Death Valley serves two objectives. It exists as empirical evidence of the various elevations seen in the landscape. Images like these, while looking scientifically at the desert, have another goal. The rise in elevation in the photograph maximizes gradations of light and dark, accentuating the austere elegance of one lone bush in the foreground. The hazy grayscale mountains in the background gently slope until they meet at some unseen point in the distance. All that we discern at this disappearing point are radiating rays of sunlight hitting the mountains and the wispy bands of clouds in the sky. Even if scientific in intent, this image creates a discernible desert aesthetic infused with the sublime - or the all-consuming awe felt when confronted with such a powerful and mysterious view.

Photographs of desert landscapes oscillate between rational vision and sublime aesthetics. The former points to a logical human eyesight that sees the desert as a subject of scientific expedition and study. On the other hand, the latter gazes at the elemental aspects of the desert that pulse with beauty. Yet, as we see, those two ways of seeing the desert are inseparable, possibly revealing a weakness in our ability to fully perceive this environment - it remains an intractable blank canvas for different ways of seeing.

The photographs in this gallery explore the symbols created to aid in the sense-making of the desert. The title Legend is a double entendre that at first glance refers to the merely informative interpretations of symbols helping travelers navigate rock formations and other notable features. A second meaning sees logical symbols as imbricated in modes of aesthetic interpretation that infuse the landscape with enculturated desires and ideals. In this gallery, there are three sets of legends that address both these registers: botany and the sublime, geology and abstraction, and landscape and orientalization.

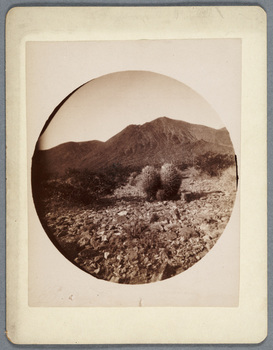

Panamint Valley, California, Enchinocactus wisilizeni in Shepherd Cañon, Undated.

Panamint Valley, California, Enchinocactus wisilizeni in Shepherd Cañon, Undated.

Botany and the Sublime

Similar to the image of Death Valley, other early photographic excursions into the desert yielded a bounty of images identifying and classifying local flora and fauna. The image at left is one of the oldest examples of botanical desert photography in the exhibition, taken in Panamint Valley, California at the end of the nineteenth century. The sepia coloring of the circular snapshot highlights the monotone rise and fall of the rough terrain. The photograph's main subject is the small clump of barrel cactuses (Enchinocactus wisilizeni) located slightly right of center. These neighboring specimens must have caught the eye of the photographer as exemplars of their kind. But something else appears in the photograph that eclipses a purely scientific reading of the image. The cactuses seem like one small part of a larger boundless landscape. The camera keeps the cactuses almost at the horizon, which augments a continuous upward and downward pull of the terrain. Framing the desert in this way amplifies its awesome boundlessness, an aesthetics interpretation visually aided by the cactuses acting as lone wanderers surrounded by their majestic scenery

Similar to the image of Death Valley, other early photographic excursions into the desert yielded a bounty of images identifying and classifying local flora and fauna. The image at left is one of the oldest examples of botanical desert photography in the exhibition, taken in Panamint Valley, California at the end of the nineteenth century. The sepia coloring of the circular snapshot highlights the monotone rise and fall of the rough terrain. The photograph's main subject is the small clump of barrel cactuses (Enchinocactus wisilizeni) located slightly right of center. These neighboring specimens must have caught the eye of the photographer as exemplars of their kind. But something else appears in the photograph that eclipses a purely scientific reading of the image. The cactuses seem like one small part of a larger boundless landscape. The camera keeps the cactuses almost at the horizon, which augments a continuous upward and downward pull of the terrain. Framing the desert in this way amplifies its awesome boundlessness, an aesthetics interpretation visually aided by the cactuses acting as lone wanderers surrounded by their majestic scenery

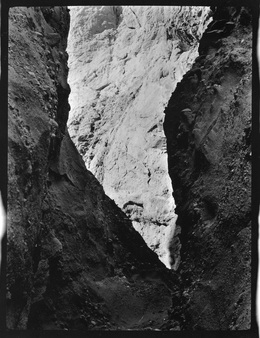

Painted Canyon, California, Approximately 1924.

Painted Canyon, California, Approximately 1924.

Geology and Abstraction

The desert's geology, like botanical imagery, was a subject of considerable interest, especially to the amateur photographer of the early twentieth century. Not only were the desert's cavernous mountain passes and rocky canyons a true automobile adventure, but its setting had remarkable visual appeal. The image at right, taken in the Painted Canyon in 1924, is one of a series of photographs in this gallery transforming desert geology into a study of abstract forms. Strikingly different from the botanical landscapes, this image provides no horizon or ground line. This lack forecloses any perspectival sense of depth or space. The photographer turns a three-dimensional landscape into a two-dimensional flat plane. While displaying a considerable visual fascination with the complex geology of the canyon, aesthetic choices hone in on the underlying geometry of its craggy angles and shadows. The force of the geometry surpasses a merely geological interest when the rock and shadow of two separate canyon walls turn into a triangular zig-zag pattern of light and dark.

The desert's geology, like botanical imagery, was a subject of considerable interest, especially to the amateur photographer of the early twentieth century. Not only were the desert's cavernous mountain passes and rocky canyons a true automobile adventure, but its setting had remarkable visual appeal. The image at right, taken in the Painted Canyon in 1924, is one of a series of photographs in this gallery transforming desert geology into a study of abstract forms. Strikingly different from the botanical landscapes, this image provides no horizon or ground line. This lack forecloses any perspectival sense of depth or space. The photographer turns a three-dimensional landscape into a two-dimensional flat plane. While displaying a considerable visual fascination with the complex geology of the canyon, aesthetic choices hone in on the underlying geometry of its craggy angles and shadows. The force of the geometry surpasses a merely geological interest when the rock and shadow of two separate canyon walls turn into a triangular zig-zag pattern of light and dark.

Thomas Davis residence, Outdoor living space, Palm Springs, California, Approximately December 1956.

Thomas Davis residence, Outdoor living space, Palm Springs, California, Approximately December 1956.

Landscape and Orientalization

At the start of the 1920s, the desert was the setting for a twentieth century orientalizing movement in American popular culture, specifically seen in design, fashion, literature, and music. Orientalism is a term with different, yet related, historical meanings. The movement in the 1920s was colloquially called "Araby," which meant products of Western culture that appropriated mainly North African and Middle Eastern themes and subjects. The image at left, a photograph of the outdoor living area of the Thomas Davis residence in Palm Springs, California, is a later example of this popular orientalizing trend. The Turkish-style rug placed under two benches, a low beverage stand, and an intricately designed magazine holder display distilled visual citations of Arabic culture. Maynard Parker, the photographer, captured this outdoor scene for the popular lifestyle periodical House Beautiful, sharing with an American audience the fusion of an expansive desert landscape and Palm Springs luxury with orientalism. Since the publication of Edward Said's influential book Orientalism in 1978, visual examples of "Araby" take on an altered meaning. For Said, the term references the history of Western colonialism in North Africa and the Middle East, where cultural appropriations of Arabic culture by the West service an unequal power dynamic between colonizer and colonized. "Araby" was a trend in the early twentieth century appearing after the frontier of the American West was deemed officially closed. One interpretation of the popularity of desert images with noticeable Arabic elements is that these orientalist aesthetics served a desire to "re-colonize" the already seized West by making the landscape "exotic" again.

At the start of the 1920s, the desert was the setting for a twentieth century orientalizing movement in American popular culture, specifically seen in design, fashion, literature, and music. Orientalism is a term with different, yet related, historical meanings. The movement in the 1920s was colloquially called "Araby," which meant products of Western culture that appropriated mainly North African and Middle Eastern themes and subjects. The image at left, a photograph of the outdoor living area of the Thomas Davis residence in Palm Springs, California, is a later example of this popular orientalizing trend. The Turkish-style rug placed under two benches, a low beverage stand, and an intricately designed magazine holder display distilled visual citations of Arabic culture. Maynard Parker, the photographer, captured this outdoor scene for the popular lifestyle periodical House Beautiful, sharing with an American audience the fusion of an expansive desert landscape and Palm Springs luxury with orientalism. Since the publication of Edward Said's influential book Orientalism in 1978, visual examples of "Araby" take on an altered meaning. For Said, the term references the history of Western colonialism in North Africa and the Middle East, where cultural appropriations of Arabic culture by the West service an unequal power dynamic between colonizer and colonized. "Araby" was a trend in the early twentieth century appearing after the frontier of the American West was deemed officially closed. One interpretation of the popularity of desert images with noticeable Arabic elements is that these orientalist aesthetics served a desire to "re-colonize" the already seized West by making the landscape "exotic" again.

|

Tour

|

Caption Information

- Panamint Valley, California, Enchinocactus wisilizeni in Shepherd Cañon, undated, 416 (39), The T.S. (Theodore Sherman) Palmer Collection, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Owens Lake, California, Looking N.W., High Sierra in background, undated, 416 (33), The T.S. (Theodore Sherman) Palmer Collection, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Death Valley, California (?), approximately 1924-1935, 400-2-7899, The Historical Society of Southern California Collection—Charles C. Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Coachella Valley, California (?), approximately 1928, 375 (574), The Automobile Club of Southern California Collection of Photographs and Negatives, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Painted Canyon, California, approximately 1924, 400-2-5469, The Historical Society of Southern California Collection—Charles C. Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Painted Canyon, California, approximately 1924, 400-2-5473, The Historical Society of Southern California Collection—Charles C. Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- The oasis of Chino Canyon toward San Jacinto, Palm Springs, California, Riverside County, approximately 1955, 310 (4223), The Eugene Swarzwald Pictorial California and the Pacific Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Rider on desert, Palm Springs, California, Riverside County, undated, 310 (4244), The Eugene Swarzwald Pictorial California and the Pacific Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Coconut Grove nightclub at The Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles, California, undated, photCL MLP 3815 (007), The Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs, and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Thomas Davis residence, Outdoor living space, Palm Springs, California, approximately December 1956, photCL MLP 1393 (071), The Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs, and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.