Caption information at bottom of page

“To take possession of space is the first gesture of the living, men and beast, plants and clouds, the fundamental manifestation of equilibrium and permanence. The first proof of existence is to occupy space.”

- Le Corbusier, The Modular: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics (1961).

Leaving No Trace Behind

A Guide to Desert Conservation

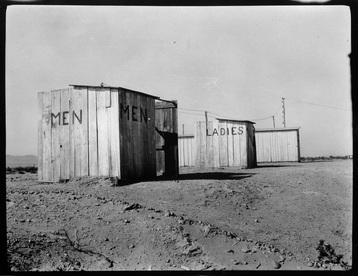

Wooden plank Men and “Ladies” outhouses, Midway, California, Undated.

Wooden plank Men and “Ladies” outhouses, Midway, California, Undated.

A seasoned traveler knows that no trace of human presence should be left behind when leaving the desert. This is the familiar rhetoric of conservationists whose policies aid in keeping the desert's unique ecology untainted by heavy traffic to protect national and state parks. While the goals of land conservation are altruistic, they do beg the question of whether or not the desert has ever really been a landscape left untouched by human activity. Le Corbusier's provocative introductory quote sheds light on this conundrum. In saying "the first proof of existence is to occupy space," the famous architect acknowledges that untouched space does not exist. Even further the quote sees life as synonymous with the possession of space. This view becomes somewhat paradoxical when thinking about the long history of seeing the desert as a harsh environment that hinders human occupation and development.

Energy is the key to unlocking the paradox of human trace in the desert. Peter S. Alagona and Clinton F. Smith assess that the desert’s energy systems, carried out both on land and sky, fuel the true power of this landscape. Solar and wind energy are the two inescapable dynamics controlling and shaping the surface sand, dust, and rock. The sun’s oppressive control during the day, and complete retreat in the night, create the extremes of temperature that effectively dry out the land. The surface heat intermingles with the hovering atmosphere, causing turbulent winds that blow through valleys, flats, and rocky passes. The problem with these energy systems lies in their excessiveness. Because the desert does not fully yield to human development, the desert's excess energy becomes unwieldy and unpredictable.

The conservationist's claim to "leave no trace behind" guides the assumption that humans can govern and control the desert. In reality the efforts of a well-informed traveler may affect the environment in some unforeseeable way. This gallery confronts the idea of “leaving no trace” with photographs revealing a history of desert development marred by human disturbances, which lead to unpredictable environmental consequences. These traces include “terraforming” the desert, making sustainable desert habitation, and casting off industrial waste.

Energy is the key to unlocking the paradox of human trace in the desert. Peter S. Alagona and Clinton F. Smith assess that the desert’s energy systems, carried out both on land and sky, fuel the true power of this landscape. Solar and wind energy are the two inescapable dynamics controlling and shaping the surface sand, dust, and rock. The sun’s oppressive control during the day, and complete retreat in the night, create the extremes of temperature that effectively dry out the land. The surface heat intermingles with the hovering atmosphere, causing turbulent winds that blow through valleys, flats, and rocky passes. The problem with these energy systems lies in their excessiveness. Because the desert does not fully yield to human development, the desert's excess energy becomes unwieldy and unpredictable.

The conservationist's claim to "leave no trace behind" guides the assumption that humans can govern and control the desert. In reality the efforts of a well-informed traveler may affect the environment in some unforeseeable way. This gallery confronts the idea of “leaving no trace” with photographs revealing a history of desert development marred by human disturbances, which lead to unpredictable environmental consequences. These traces include “terraforming” the desert, making sustainable desert habitation, and casting off industrial waste.

First can of striped bass being planted, Salton Sea, Approximately January 1930.

First can of striped bass being planted, Salton Sea, Approximately January 1930.

Located southeast of Palm Springs, the Salton Sea is hard to miss. Stretching 400 square miles at its zenith, the large desert body of water is a prominent feature of the Imperial and Coachella Valleys. Today, a visit to the Salton Sea is as simple as pulling of off highway 86 and slowly driving through citrus groves until finally arriving at the edge of the "sea." The sound of birds is overwhelming at this point. Not surprising, the Salton Sea, since its filling in 1905-06, is a sanctuary for many species of birds that enjoy the water and the fish populating it. However, this scene at the Salton Sea shore is overshadowed by the presence of industrialized agriculture and the smelly, grimy runoff of pesticides and other chemicals. The Salton Sea therefore is a desert feature with two conflicting sides. It is both a natural and unnatural occurrence. The Salton Sink - the basin now covered by water - was part of an ancient lake and watershed. After the Colorado River levees broke in the early twentieth century the basin filled. The mishap generated questions about what to do with this newly formed desert sea. Terraforming was a way to make the Salton Sea an attractive new destination for tourists and real estate developers. The image at left is a photograph from 1930 showing the first can of striped bass being seeded in the water. Making the Salton Sea a fishing epicenter was one goal of terraforming - building the ecosystem of the desert to support species and plants not typically found in these arid locations. The sea's transformation into a "desert riviera" made way for current ecological concern and apocalyptic paranoia. No longer fed by fresh water, the Salton Sea is now dealing with a hypersalinity crisis. The ever increasing evaporation of the sea compounds this problem. Irrigation runoff is the only water that enters into the mass, which introduces hazardous chemicals into the ecosystem. The birds and fish that once flourished in the Salton Sea are dying in great numbers from toxic water and an infestation of protozoan parasites. These real environmental dangers, and the unforeseen future of the Salton Sea, are the consequence of human traces in the desert. Efforts to terraform the desert after a chance levee disaster began as ways of controlling the environment. The sea's current state exceeds expectation in the worst sense and, in doing so, reveals the impact that human traces have on future generations.

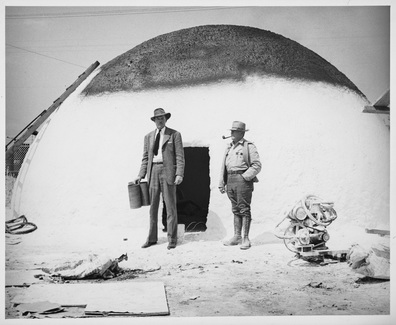

Airform construction.

Airform construction.

Architects working in arid landscapes, such as the desert modernists in Palm Springs, cherished designs that seamlessly blended landscape and living space. Desert modernism rose in popularity during the 1950s and 1960s because its architecture embellished the landscape. Simple, clean, and geometric lines and shapes highlighted a modern structure's beauty within an environment consisting entirely of harsh sunlight, flat expanses, and ragged rocks. Despite this goal, these structures were not sustainable. Heavy use of glass made temperature regulation a necessary energy expense. Structures were built with industrial and commercial materials not suitable for desert wear and tear. The airform design of Wallace Neff, a Southern California architect, is a lesser known movement in desert architecture. Slightly predating desert modernism, the airform was Neff's innovative response to issues of sustainability in harsh environments. Neff's airforms could be quickly and economically constructed. During the process, a large inflated rubber balloon is set onto of a circular concrete foundation. Scaffolding is placed around the balloon for workers as they spray gunnite concrete over it, thus the origin of the term "air form." Neff's structures then dried with astonishing durability. The balloon is deflated and the interior customized to the buyer's wishes. The image at right is a photograph of an airform in mid-construction. It shows the common application of white pigment to the dried concrete. The white allowed the airform to self-regulate temperature by reflecting light, keeping the interior cool during the day and trapping warmth at night. Neff wanted the airform to be a low cost and energy option for living in different environments. The structures were especially well suited for desert living, because the design could recycle the arid terrain's excessive energy. Although Neff's construction company, the Airform International Construction Company, was busy with commissions, the design never was as popular or iconic as desert modernism. The visionary hope that the airform would change the way humans impacted their environment was cut short by the construction boom spurred in part by these modernists, their structures, and the general development of Palm Springs.

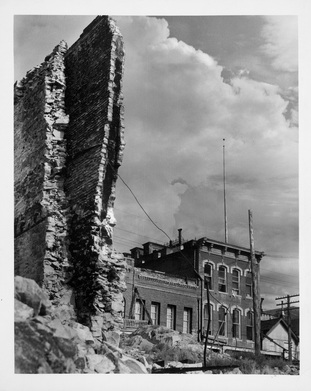

Ruins in Virginia City, Nevada, Undated.

Ruins in Virginia City, Nevada, Undated.

The most prominent human feature in the desert is industry. The earliest desert economies were mining and agriculture. These are still prolific industries, but now commingle with military testing of nuclear energy, wind turbines, solar panel fields, uranium storage, and droneports. The mark of these industries on the desert landscape is immediate and lasting, even after these activities have ceased. The image at left is a photograph of the ruins of Virginia City, Nevada. This location was a prominent early twentieth century boom town that popped up in the desert around the famous Comstock Lode. Silver ore was the raw mineral extracted at this site. Virginia City is now a desolate industrial ghost town. Empty buildings stand next to crumbling edifices, seen in the image at left. The quick exhaustion of the Comstock silver ore turned this once growing city into a graveyard. Virginia City is a case study for the many boom towns established in the desert. These sites - Virginia City, Rhyolite, the Salton Sea's North Shore, even Palm Springs - exemplify the ebbs and flows of industry and population. This is a history of rapid occupation and abandonment. Yet the traces of human inhabitation and industry do not leave. They rather act as a palimpsest when every trace extends into the next. This is a process that shapes our very understanding of the desert landscape, and allows us to question whether this terrain was ever really pristine - maybe the desert was fabricated all along.

|

Tour

|

Caption Information

- Wooden plank Men and “Ladies” outhouses, Midway, California, undated, 400-2-6030, The Historical Society of Southern California Collection—Charles C. Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Date palm grove with bags hanging on trees, Riverside County, November 23, 1948, 400-2-5901, The Historical Society of Southern California Collection—Charles C. Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- First can of striped bass being planted, Salton Sea, approximately January 1930, 375 (558), The Automobile Club of Southern California Collection of Photographs and Negatives, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Man and woman looking out, Salton Sea, approximately 1934, 375 (949), The Automobile Club of Southern California Collection of Photographs and Negatives, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Painting of exterior of unrealized airform structure, unknown artist (possibly Wallace Neff), undated, Wallace Neff papers, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Airform construction, Wallace Neff Papers, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Airform structures, Exterior, Loyola University, approximately 1941, photCL MLP 0886 (001), The Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs, and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Gold Hill, Virginia City, Nevada, undated, 310 (7679), The Eugene Swarzwald Pictorial California and the Pacific Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Ruins in Virginia City, Nevada, undated, 310 (7678), The Eugene Swarzwald Pictorial California and the Pacific Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Bottle house, Rhyolite, Nevada, undated, 310 (7689), The Eugene Swarzwald Pictorial California and the Pacific Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Close-up of wall of house of whiskey bottles, Rhyolite, Nevada, undated, 310 (7690), The Eugene Swarzwald Pictorial California and the Pacific Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.