Caption information at bottom of page

"Until they attempt to pry gender from the discards of the past, archaeologists of the West will continue to assume that the region's settlement by Euro-Americans took place by and for the benefit of its male populations."

- Catherine Holder Spude, "Brothels and Saloons: An Archaeology of Gender in the American West" (2005).

Navigating Desert Byways

A Guide to a Gendered Environment

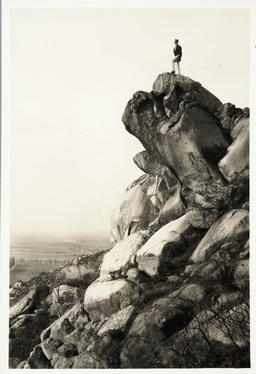

Orange Heights Park, Corona, Riverside County, Approximately 1920s.

Orange Heights Park, Corona, Riverside County, Approximately 1920s.

A history of the American desert is incomplete without a discussion of the many roads and byways constructed to promote travel to this arid landscape. This is a period in the development of the desert after its initial exploration in the early twentieth century. Mapping the desert was important, because it carried with it the idea of reinvention. Roads quite literally changed the desert terrain, marking it with official pathways promoting safer movement to burgeoning city centers and notable natural sights. Yet these roads contained another type of reinvention. Road tripping through the desert is an activity that allows for self-exploration - or even a transformative experience. The desert's ability to reinvent identity is not new. Many of the world's deserts became source of ascetic traditions and spiritual events. But unique to the American desert are ways in which mapping the terrain, for the first time, allowed the built environment - here the roads scouring the land - to rival or surpass the natural one. Mapping the desert was the first step in turning the arid environment into what Joseph Masco calls a "fantasy playground." This suggests that the wonder and awe found in this setting cannot be dissociated from amazement with one's own mapping and reinvention of the desert.

The photographs in this gallery investigate mappings of the desert landscape, and the self-fulfillling ideologies fueling this "fantasy playground." Commenting on the establishment of campsites, Charlie Hailey remarks that mapping reduces the frontier to a human scale. The fantasy is activated when reinventing the desert via roads or campsites consequently produces human precariousness. This gallery explores desert navigation as an activity that specifically "maps" unstable performances of gender identity onto the terrain. The photographs in this section show the desert as an environment containing different expressions of masculinity and femininity. The former is a common trope for the desert, particularly the masculine-centered settlement of the wilderness or frontier. Less examined are examples where femininity maps itself on the desert through the activities of female explorers and workers.

The photographs in this gallery investigate mappings of the desert landscape, and the self-fulfillling ideologies fueling this "fantasy playground." Commenting on the establishment of campsites, Charlie Hailey remarks that mapping reduces the frontier to a human scale. The fantasy is activated when reinventing the desert via roads or campsites consequently produces human precariousness. This gallery explores desert navigation as an activity that specifically "maps" unstable performances of gender identity onto the terrain. The photographs in this section show the desert as an environment containing different expressions of masculinity and femininity. The former is a common trope for the desert, particularly the masculine-centered settlement of the wilderness or frontier. Less examined are examples where femininity maps itself on the desert through the activities of female explorers and workers.

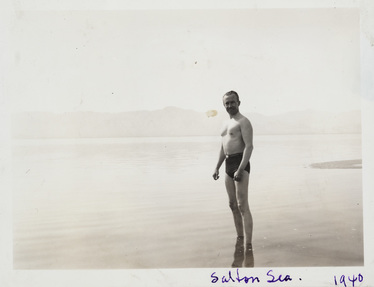

Ulysses S. Grant IV and other UCLA geologists, Salton Sea, Approximately 1940.

Ulysses S. Grant IV and other UCLA geologists, Salton Sea, Approximately 1940.

"No longer comfortable with the familiar in western American history - arid environmental determinism, frontiers giving way to post-frontiers, national character expressed as western masculinity - historians now seek to defamiliarize the field and its icons," says William Deverell in a defense of new historical approaches to reading the desert and the Western frontier. Notable is his remark that nationalism, masculinity, and the mapping of the American West are familiar topics. The image at left is a portrait of Ulysses S. Grant IV swimming in the "desert riviera" of the Salton Sea located just southeast of Palm Springs. This image captures several recursions of Western masculinity. Nationalism infuses the male figure by way of birth as the grandson of Ulysses S. Grant, 18th President of the United States. Grant IV became a geologist and headed West, seen here on a 1940 expedition with several other scientists from the University of California, Los Angeles. Grant's stance - standing stiffly upright with arms firmly clenched and eyes meeting the camera head on - visually dominates the image. The shallow water and the distant mountain range fall away in the photographic framing of this imposing man. While scenes such as these are common masculine depictions in the desert, one can note an element of instability fueling such a display of frontier prowess. Enjoying the waters of the Salton Sea is an activity provided by human mapping. The desert rivera was the product of human mishap, and later terraforming, when the Colorado River levees broke in 1905-06, which filled the Salton Sink. This almost entirely invented environment sets the stage for Grant's personal display of nationalism and masculinity, suggesting that the Salton Sea is not the only fabricated aspect within the image. Mapping the desert reveals its extreme malleability and precariousness, allowing us to question, or defamiliarize, the masculinity and nationalism expressed in these environments.

Miss Elizabeth Runyan, Nurse at Contractors’ General Hospital, Colorado River Aqueduct, Approximately 1932-1934.

Miss Elizabeth Runyan, Nurse at Contractors’ General Hospital, Colorado River Aqueduct, Approximately 1932-1934.

In another portrait, seen at right, Miss Elizabeth Runyan drives her shiny truck to and from the Colorado River Aqueduct's general hospital. Her crisp white uniform notes Miss Runyan’s occupation as a nurse for the contractors at the building site. There are parallels between the portraits of Ulysses S. Grant IV and Elizabeth Runyan. Both of these individuals take part in the development of the Colorado River - the failure of its levee and the creation of its aqueduct. Curiously beneath each subject there is a similar shadow reflection - on the water below Grant and on the chrome below Runyan. These shadows allow for a fascinating reading of gender in both photographs. In the water under his feet, Grant's own shadow extends his physical body beyond the limits of the photograph's frame. The dark puddle visually connects Grant's body to the surrounding Salton Sea. The diffusive quality of the surrounding environment - the lack of clear distinction between water, mountain, and sky - maps his masculinity directly onto this invented environment. The shadow bifurcated by the car door under Runyan is not her own, but rather the reflection of the male photographer whose wide-brimmed hat hints at his sex and gender. Surrounding Runyan is the curved square frame of the truck, which cuts her off from the shadow and makes her visually recede from the masculine constructed environment so easily adopted by Grant. A feminine mapping of the desert is here shown as highly active, yet curiously disassociated from the "manning of the West."

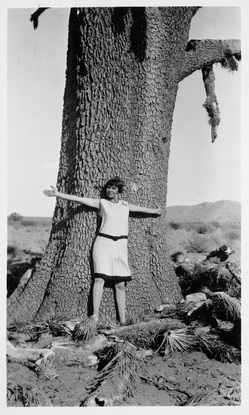

“A Venerable Joshua Tree,” Approximately February 1929.

“A Venerable Joshua Tree,” Approximately February 1929.

Images of women navigating the American desert proliferate the photography archives of The Huntington Library. The portrait of Elizabeth Runyan and the image at left, a 1929 member of the Automobile Club of Southern California, are two examples where feminine activities in the desert transgress the common narrative of gender in the Western frontier. Rather than guided by nationalism and masculinity, these women seem to navigate the landscape on their own terms. The photograph at left shows a woman in front of a "Venerable Joshua Tree." Its shear size peaked the interest of the woman and her automobile convoy, spurring her to use her arm span to display the incredible girth of the trunk. Mapping the landscape according to the dimensions of the feminine form is an alternate to the view that navigating the West is a purely masculine prerogative. Feminist historians of the West are still developing the implications of this defamiliarized gender reading. For Catherine Holder Spude, records of feminine activities in the desert are much maligned and in need of acknowledgement. The immense visual documentation of women in the desert at The Huntington Library suggests that there is another history of the American desert waiting to revise our common understanding of this landscape. There is however one thing that remains clear in regard to the desert and gender. Feminine activities in these environments are so negligible in the historical record that mapping oftentimes just becomes "manning the West." Pinpointing the moments when nationalism, masculinity, and the desert break down within the "fantasy playground" is a method for finding desert femininity.

|

Tour

|

Caption Information

- Orange Heights Park, Corona, Riverside County, approximately 1920s, 310 (3694), The Eugene Swarzwald Pictorial California and the Pacific Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Yucca in bud, undated, 276 (1868), The Charles Francis Saunders and Mira Culin Saunders Collection of Photographs and Negatives, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Unidentified man standing over barrel cactus drinking water, Riverside County, undated, 276 (1825), The Charles Francis Saunders and Mira Culin Saunders Collection of Photographs and Negatives, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Ulysses S. Grant IV and other UCLA geologists, Salton Sea, approximately 1940, photPF 20205, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Miss Elizabeth Runyan, Nurse at Contractors’ General Hospital, Colorado River Aqueduct, approximately 1932-1934, 375 (843), The Automobile Club of Southern California Collection of Photographs and Negatives, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Palm Springs, California (?), March 31, 1949, 400-2-5915, The Historical Society of Southern California Collection—Charles C. Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Women picking desert flowers, Palm Springs, California, Riverside County, approximately 1927, 310 (4328), The Eugene Swarzwald Pictorial California and the Pacific Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- Palm Springs, California (?), March 31, 1949, 400-2-5917, The Historical Society of Southern California Collection—Charles C. Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- “A Venerable Joshua Tree,” Location unknown, approximately February 1929, 375 (702), The Automobile Club of Southern California Collection of Photographs and Negatives, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

- “A Venerable Joshua Tree,” Location unknown, approximately February 1929, 375 (702), The Automobile Club of Southern California Collection of Photographs and Negatives, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.